Building Site Risks and How to Overcome Them

With long timelines and many moving parts, building projects present plenty of risks. Site conditions can be one of the riskiest components of a project, and often, extra work is required to prepare the site for construction.

With over 40 years of experience, we’ve seen it all—from contaminated sites to inadequate soil conditions. The best approach is to consult geotechnical engineers, civil engineers, and other third-party experts in the early stages of a project and work with your architect to mitigate risk.

If starting a building project, understanding potential site risks is crucial. This article will discuss some of the most common building site risks and how to overcome them.

Soil Contamination

Contaminated soil is a common problem with urban building sites. Typically, a geotechnical engineer will identify the risk of this issue.

Before your architect starts design work, the geotechnical engineer will visit the site, take soil samples, and create a report. The report will pull information about former site uses, identifying the risk of contamination. Often, sites previously housing gas stations, dry cleaners, and industrial plants contain some contamination.

Contaminated sites require remediation before construction can begin. The level of remediation depends on the severity of the problem. For example, removing underground storage tanks or leaking gasoline can require extensive site work.

Contaminated soil removal and remediation at Des Moines Municipal Services.

No matter the situation, remediation ensures hazardous materials do not seep into the building and endanger occupants.

Conducting a geotechnical survey before purchasing the site is the best way to mitigate risk. If you purchase a contaminated site, remediation can be a part of the negotiation process.

Contaminated sites can also present additional funding. In Iowa, for example, brownfield redevelopment projects are eligible for tax credits.

Existing Structures

Existing structures are also a common problem with urban sites. If the site had a previous use, you may encounter building footings beneath the soil.

A ground-penetrating radar scan can show solid matter beneath the surface and identify any problems you may encounter. However, this service can be an additional cost and is not always necessary.

Instead, your architect may recommend a contingency or allowance to cover the potential removal. Planning for this scenario helps protect your budget.

Similarly, you may encounter problems with other buildings. If your building goes below the bearing height of neighboring buildings, you risk disrupting their foundations. As such, you may need to erect temporary retainage systems like sheet piles.

This issue should be well-known during the design process, and your architect should factor the cost of support systems into your construction budget.

Inadequate Soil Conditions

While contaminated sites and existing structures are common issues in urban areas, greenfield sites also present risks. Some sites may contain inadequate soil conditions for the type of structure you plan to build.

Like site contamination, inadequate soil conditions will be identified in a geotechnical report. The geotechnical engineer will drill into the ground and take samples of soil and bedrock, a process known as soil boring. Analyzing these samples determines if the site can support the proposed structure.

Although a geotechnical survey occurs early in the process, the geotechnical engineer should understand the project’s general requirements when analyzing the soil. Explaining the building’s height, size, and planned construction techniques will lead to a more accurate analysis.

The geotechnical report will also identify soil and clay types within the area. For example, in Eastern Iowa, expansive clay is common. If your site is at-risk for these soil conditions, your architect may recommend a contingency to cover the cost of removing soil during construction.

Occasionally, building sites contain decomposing organic matter, especially if the site housed a garbage dump or burn pit. Like expansive clays, organic matter must be removed before construction can begin. By studying the site’s history, a geotechnical engineer can identify the risk of this issue.

Keep in mind, the geotechnical report only identifies the potential for these issues. Before breaking ground, it is difficult to know for certain what lies beneath, but the report helps you understand the risks and budget accordingly.

Floodplains and Water Levels

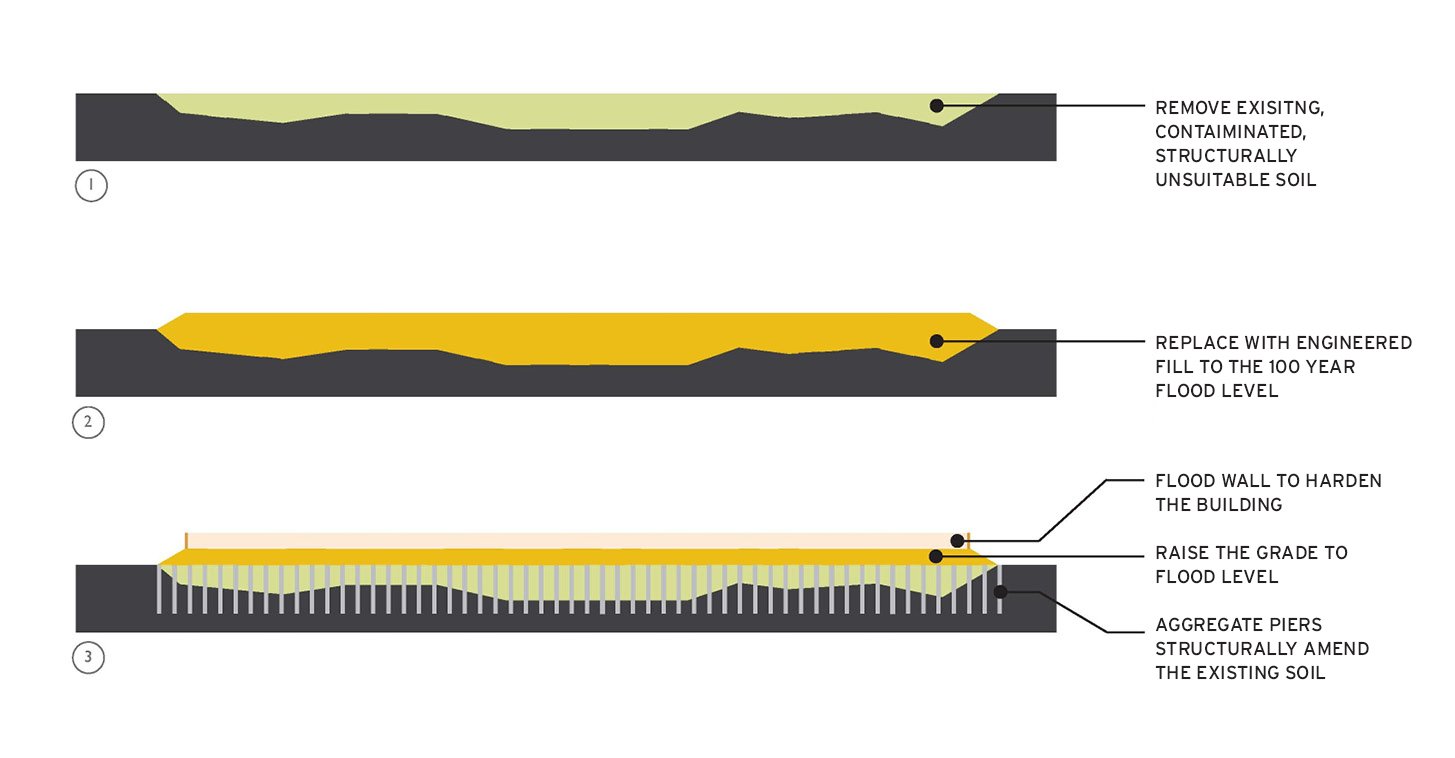

Some sites present additional environmental risks, especially those located in floodplains. Generally, it is best to avoid floodplains when selecting a building site. However, if you choose to build in a high-risk area, you will need to take additional steps to protect your building.

Local jurisdictions will have requirements for the height of occupied levels above a floodplain. To meet these requirements, you may need to raise the foundations, fill the site to the necessary level, or design for dry or wet flood-proofing.

Raised occupied levels at Beckwith Boathouse.

Dry flood-proofing may include removable flood walls or gates, and wet flood-proofing allows water to flow through the building. Typically, wet flood-proofing is used for parking structures, with mechanical and electrical systems above base flood elevations.

Even if your site is outside a floodplain, it’s important to know its water level. The water table sits higher in some locations, posing problems for basements and other underground structures. Early research into site conditions can help your design team find ways to protect the building.

Natural Habitats

Occasionally, building sites contain natural habitats for protected species. An ecologist can help identify these habitats in the early stages of a project.

In some cases, natural habitats can affect construction timelines. For example, Indiana Bat habitats cannot be disturbed during mating season. You may need to delay your construction timeline to protect mating species, as was the case for Iowa City Public Works.

By researching the site’s ecology early in the process, your architect can plan the site design and construction timeline to reduce the risk of disturbing wildlife.

Easements

Lastly, some building sites contain easements. An easement is a legal situation where another person or organization has the right to use the land for a specific purpose.

For example, some sites may contain a gas or electrical line owned by a utility company. In other situations, a municipality may own a storm sewer line beneath the site or have land access rights.

Depending on the situation, an easement can create design and construction constraints. We recommend analyzing these easements during site selection to determine the site’s viability for your project.

Prepare for Your Building Project

Every building site presents some risks. While contamination and existing structures are common problems in urban areas, greenfield sites can contain inadequate soil conditions and wildlife habitats.

Taking the time to study the site before starting design work is the best way to mitigate these issues. Geotechnical engineers, civil engineers, and ecologists can help identify potential problems, and your architect can help plan contingencies and allowances.

Keep in mind, geotechnical engineering and other third-party services are outside an architect’s scope. Although necessary, these services are an additional project cost that you will need to account for at the beginning of your project.

Before starting a building project, it helps to understand the project costs you will encounter. Learn more by reading about the differences between project and construction costs.