Community Collaboration Creates the GuideLink Center: A Case Study

Located in Iowa City, the GuideLink Center provides immediate care for individuals facing emotional, mental health, and substance abuse challenges. It offers a much-needed alternative to jails and emergency rooms in crises and helps individuals access follow-up resources.

Since its opening in 2021, the GuideLink Center has helped thousands of individuals across Eastern Iowa. We are proud to have been a part of the project and feel inspired by its impact on our community.

The design process brought together various community groups, including medical professionals, politicians, law enforcement, and crisis service experts. Drawing from their experience and expertise, these groups were able to elevate the project’s potential.

This article will discuss the GuideLink Center’s collaborative design process and explain how these early discussions led to design decisions.

Background: Responding to a Community Demand

The GuideLink Center was born out of a community demand for rehabilitation services as an alternative to retribution. Johnson County jails were overcrowded, and after an unsuccessful bond referendum campaign for a new facility, the county asked the community for feedback.

The Johnson County Board of Supervisors formed a committee with experts from various interest groups, including psychologists and medical professionals from the University of Iowa, law enforcement officers from Johnson County communities, and mental health service providers.

The group explored the possibility of creating a jail alternative, setting the foundation for the design process ahead.

Programming: Determining Necessary Spaces

With few precedent projects available, the group drew from their collective expertise to determine the facility’s programming requirements. The goal was to find solutions that would meet multiple community needs.

Legal requirements dictated the relative size of the facility. Knowing the facility could have no more than 16 beds, the group began discussing how to best provide mental health and substance abuse treatment.

Some stakeholders suggested a sobering space, and others petitioned for a winter homeless shelter that could double as a community shelter in emergencies. The group also decided to include a dedicated respite space for first responders.

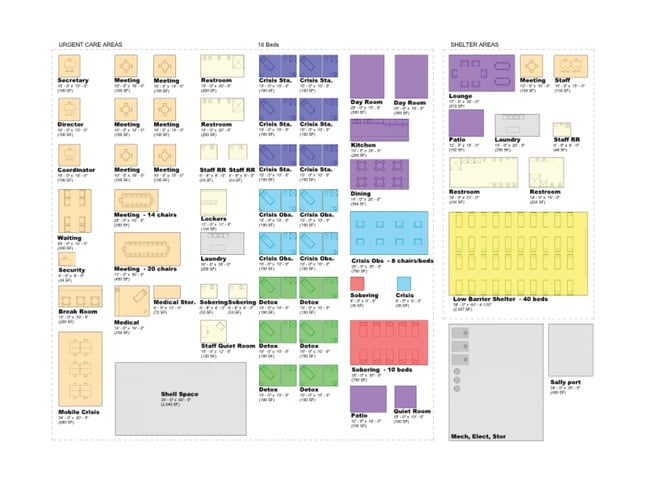

Programming elements for the GuideLink Center.

In a planning workshop, project stakeholders diagrammed potential layouts with moveable blocks. This exercise helped the design team better understand the necessary adjacencies between spaces.

Preliminary diagrams divided the program into three sections:

- Administrative space

- Care space

- Winter shelter

As these diagrams became more detailed, the team created a rigorous, modular layout to connect each section and provide clear sightlines throughout the facility.

Floor plan with programming elements organized for simplicity and user experience.

Investing in On-Site Energy Production

Initially, the project’s stakeholders considered reusing an existing building but struggled to find the right location.

Instead, they opted for an underutilized site near Shelter House and Cross Park Place to create connectivity between various community services. The GuideLink Center’s focus on mental health recovery—and its inclusion of a winter shelter—aligned well with Shelter’s House’s goal to help people move beyond homelessness.

The project was funded and constructed by Johnson County with matching donations from vested parties. Although the county would provide construction expenses, a third-party health provider would oversee ongoing operations.

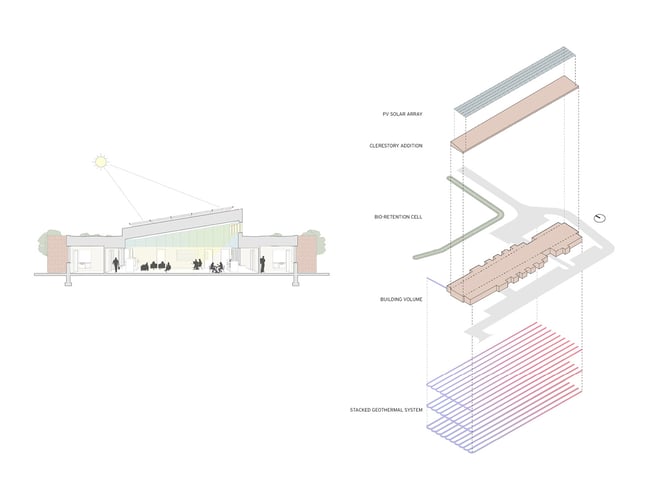

This created a unique opportunity to invest in renewable systems. The goal was to maximize the initial budget’s potential and find ways to reduce operating costs.

The project used residential style wood construction, which is less expensive than steel construction associated with commercial projects and allows for a wider bidding environment. This choice allowed for investments in on-site energy production, including a photovoltaic array and geothermal heating and cooling.

The photovoltaic array on the south-facing sloped roof supplies nearly all the facility’s electricity demands. Mini-split heating and cooling units are also included in each patient room, giving occupants individualized control over their thermal comfort.

South-facing solar panels and geothermal heating and cooling.

Creating a Welcoming Interior

Extra care was taken in the interiors to balance client comfort with security and durability.

Glass partitions separate the administrative spaces from the care facility, creating clear sightlines in all directions. The facility’s openness allows the staff to passively monitor clients and improves wayfinding.

Glass partitions provide clear sightlines throughout the facility.

Smaller spaces like break rooms, day rooms, and triage rooms line the facility’s perimeter, and larger spaces are placed in the center of the building. Larger spaces are lit from north-facing clearstory windows.

In mental health crises, patients often benefit from relaxation and sleep. The northern light is easier to control than direct southern light and creates a calming atmosphere.

Throughout the interior, the design team followed the principles of trauma-informed design. Residential finishes like wood look floors are used to minimize sterile connotations with institutional buildings.

Keeping with trauma-informed design principles, the facility also features natural, cool colors. The ceilings of patient rooms are painted, and common areas have colored acoustic panels.

Painted ceilings in patient rooms.

Impact-resistant gypsum walls at the occupant level are painted a soft white to reduce maintenance costs. By limiting color to the top of the walls, the staff can touch up high-traffic areas with a single paint color.

While the facility performs with institutional durability, it feels home-like. Patients enter an intuitive, welcoming, and therapeutic environment.

The GuideLink Center’s Impact

The GuideLink Center is an example for other communities looking to decrease pressure on jails and emergency rooms. It fills a necessary gap in care by helping those in mental health and substance abuse crises.

The Center opened in February of 2021 and expanded its services gradually. According to The Gazette, the Center had 1,175 patient encounters in its first year of operations. Nearly half of those were walk-ins.

The facility’s success is linked to its collaborative design process that drew on the expertise and experience of various interest groups. Through knowledge sharing, the committee created a project that targeted multiple community needs beyond the initial demand for a jail alternative.

Community engagement is foundational to any successful building project. To learn about another project that met multiple community needs, check out our case study on Lone Tree Wellness Center.